By David Salazar (For 5.11.12 performance)

By David Salazar (For 5.11.12 performance)I will confess that until a week ago, "Vec Makropulos" (or "The Makropulos Case", or "The Makropulos Affair," or "The Makropulos Secret," or "The Makropulos Thing") were not in my plans at all. Sometimes you grow into a certain repertoire and isolate yourselves from other potential works of art because you attach a certain stigma to them. Music of the 20th Century has always been a tough sell for me (save for Shostakovich, Prokoviev, Strauss and a few others not coming to mind at the moment) and as a result I have generally found myself avoiding the modern operas that the Met has offered.

This past fall, I got the opportunity to see Phillip Glass' "Satyagraha" and realized what I had been missing out on. I lament not finding the time to make "Billy Budd" a part of my schedule this past week, but was excited at the prospect of Janacek's penultimate work.

And I was certainly rewarded. Combining science fiction, Hitchcock, and a haunting music from Leos Janacek, "Vec Markopulos" is one of opera's best kept secrets. Or at least it was for me. And the Met's performance (the last one in the run) added all the necessary ingredients to elevate the work to an even greater level of sublimity. A great conductor, a strong production, great direction, a strong supporting cast, and of course: a fearless diva to take on the role of the longest-living diva literature has ever known.

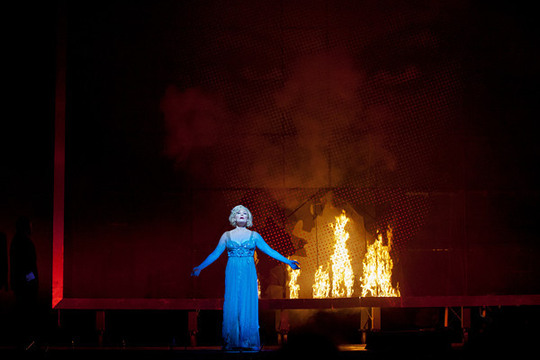

In my opinion, Elijah Moshinsky is one of the great stage directors of the past generation. His productions are generally in the traditional mold, but attention to detail is NEVER lacking in any of his work. I made note of his still potent production of Verdi's Nabucco earlier in the season, but I found the production for "Vec Makropulos" all the more imposing. The production is of course infamous for the tragedy that occurred during its premiere in which Richard Versalle sang the words "You can only live so long," had a heart attack and fell 20 feet from a ladder. I would like to note that the translations in the subtitles now read "Nothing lasts forever" and Tenor Alan Oke did not sing from the top of the ladder. The main curtain is a giant purple panel with tons and tons of indecipherable writing. The "curtain" comes up and we are shown a panel in the back covered by a large sheet. A group of people come on stage and remove the curtain to reveal the face of a woman (the secretive figure around which the work revolves). The curtain descends and then later goes back up to reveal a stark, cold, claustrophobic, steely law office with rows and rows of filing cabinets reaching toward the sky. The second act takes place at an opera house after a performance, but we are watching the stage. A giant sculpture of a Sphyinx dominates the staging either implying "Aida" as the opera being performed (I kid), or hinting at the ancient nature of the works protagonist. Only diva Emilia Marty utilizes said Sphinx as her resting place. Finally Act 3 brings us to a hotel though it looks more like an apartment with massive glass windows that would overlook a city from great height. In this case there is no city, but instead a blue background with a pair of eyes looking into the room. One could easily connect them with the eyes from the beginning of the opera, but given the action that comes in this scene, I would venture toward a more darker interpretation of these eyes. As the tragic ending of the work beckons the curtain comes again, finally revealing its significance to us (it is a formula meant to give eternal life) and eventually comes up again for a stunning finale that literally explodes with flames. It kind of reminded me of Grandage's Don Giovanni from earlier this year with fire and doors opening and closing to often reveal nothing new. In this case, the Moshinsky production never left you feeling cheated.

I will also admit that Karita Mattila's recent forays into the Italian Repertorie (Tosca, Manon Lescaut among others) has left me highly unsatisfied. But on this evening she showed me why she's still maintains a strong international career and has been hailed as one of the great singing actresses in the world. As cliche as this might sound, Mattila was Emilia Marty (or Eugenia Montez, or Elina Makropulos, or Ellian McGregor, etc). There came a point in the performance where I wasn't paying attention to the singing as singing. It was simply the extension of a live being on stage. Confidence was exuded from the first entrance as Matilla played on all of her charm and sexuality to seduce not only every man on stage, but every person in the audience. As despicable a character (if you think Turandot's cold, you should see Marty's response to a suicide committed for her) as she could be at times, it was impossible to hate her. And when she faces her personal tragedy head on at the work's conclusion (and by extension humanity) one could not feel anything but compassion and wondering. The ending of the work plays on the soprano's lyrical abilities in a way the rest of the work does not, and Matilla's voice soared with incandescent purity. Transfiguration is a word that comes to mind in the final moments of Matilla's performance.

I will also admit that Karita Mattila's recent forays into the Italian Repertorie (Tosca, Manon Lescaut among others) has left me highly unsatisfied. But on this evening she showed me why she's still maintains a strong international career and has been hailed as one of the great singing actresses in the world. As cliche as this might sound, Mattila was Emilia Marty (or Eugenia Montez, or Elina Makropulos, or Ellian McGregor, etc). There came a point in the performance where I wasn't paying attention to the singing as singing. It was simply the extension of a live being on stage. Confidence was exuded from the first entrance as Matilla played on all of her charm and sexuality to seduce not only every man on stage, but every person in the audience. As despicable a character (if you think Turandot's cold, you should see Marty's response to a suicide committed for her) as she could be at times, it was impossible to hate her. And when she faces her personal tragedy head on at the work's conclusion (and by extension humanity) one could not feel anything but compassion and wondering. The ending of the work plays on the soprano's lyrical abilities in a way the rest of the work does not, and Matilla's voice soared with incandescent purity. Transfiguration is a word that comes to mind in the final moments of Matilla's performance.Longtime Met fixture Richard Leech had a strong outing as Albert Gregor (Emilia Marty's Great-great-great-great-grandson, as she puts it). Of all of Marty's suitors, he is by the far the most ardent and Leech's bright tenor certainly rang with unbridled passion and abandon as he confessed his love for Marty on numerous occasions, often pushing his voice to the brink. Johan Reuter was the contrast as Marty's other main suitor Jaroslav Prus. He sang elegantly and with calculation as the more frigid suitor. However, his rage came to the forefront as he chided Marty's coldness toward his only son's suicide. Bernard Fitch added warmth as Count Hauk-Sendorf, Marty's lover 50 years ago. Young Singers Matthew Plenk and Emalie Savoy as Janek and Kristina showed great potential.

Next to Matilla, Conductor Jiri Belohlavek was the evenings other star. He took Janacek's complex score head on with incredible detail to its rhythmic demands. The work hints at lyricism early on and as the mystery surrounding Marty unravels, the music's lyricism "evolves" until Lyricism comes to the forefront in the work's closing moments. Belohlavek elicited some of the most gorgeous string playing heard at the Met in a while as the violins caressed the audience during the opera's overture.

This is another one to add to the list of opera's not HD'd that should have been. It had all the elements for a successful projection across the world: tremendous cast, intelligent production, great conductor, and an opera with a film plot that would go over very well with any audience.

If there is one lesson to learn from "Vec Makropulos" it is to never overlook any work presented. It is certainly one of the better performances of year and a wonderful way to close out the Met Season.

This was the best production at The Met last year ! Can't say enough about it.

ReplyDeleteOne of the few productions that has an actual plot too.